Women in tech, a computer marriage, and Y2K in 1973

Delightful news stories from the history of technology and the humans who use it.

Hi! Welcome! Before getting into this week’s content, a PSA: this project also has an Instagram account. If you like your history in picture form, check it out.

Now, onto the main show.

Women in tech

In the last newsletter, I shared a story about the pivot point in the 1980s when the number of women studying computer science began to decline.

So it’s worth noting that the decade prior was a boon for women in “the computer profession.” This article estimates that, between 1960 and 1969, the “feminine ranks” in programming swelled from 2% to 25%.

Why? According to the article, part of it was disillusionment with the “glamour jobs” in publishing and advertising that women might have sought in the past. (Young professionals in those industries would “wind up doing dreary routine typing in an obscure corner of that big slick firm and feeling like Cinderella without a godmother,” the piece claims.)

But there was also the appeal of the tech industry, which offered “plenty of independence coupled with high challenge,” as well as “a five-figure salary.” Trainees were paid $7,000 a year, or about $50,000 in 2021 dollars. With four years of experience, that figure went up to $18,000 to $25,000--or $125,000 to $175,000 in 2021.

The piece profiles Edie, a 26-year-old senior systems analyst. She was, in 21st-century parlance, a baller: “Edie hasn’t eaten a meal in her luxury East Side Manhattan apartment for three years. Date or not, it’s a different restaurant each night. She can’t recall the last time she scoured her sunken bathtub. There’s a maid in each day to do things like that.” She also drove a sports car: a red Morgan that might have looked something like this.

“I really can’t spend all I make,” Edie said. “And I assure you, I try.”

Psssst. Are you new here? Liking it so far? Subscribe to get new posts in your inbox.

Portable computers

Old computers were big. Everyone knows that. The computer I’m using to write this, on the other hand, is small. You didn’t know that, but you probably assumed.

The early days of portable computing were wild. Some “portables” weren’t really portable, weighing over twenty pounds and featuring a handle attached to the body to, you know, suggest portability. Others were, indeed, portable—this 1981 article is about units that fit in briefcases—but they weren’t necessarily computers as we think of them. These “computers” consisted of components like keyboards and modems (portable) that you could connect to peripherals like TVs or phone lines (decidedly not portable). Still: the article calls them “little mini marvels” and closes with this zinger: “Sound farfetched? So did horseless carriages and flying machines.”

Computer strike

On the morning of July 19, 1973, dozens of computers all over the world refused to turn on. Now we have a word for that sort of thing—“outage”—but back then, people defaulted to an anthropomorphic metaphor: the computers were “on strike.”

IBM, who manufactured the delinquent machines, wrung their hands (“we have no factual information that it even happened”), leaving the operators to find a fix for themselves. Which they did: they figured out they could solve the problem by telling the computers that “it wasn’t really July 19, 1973.”

It’s unclear why that worked. People theorized that the failure was due to a security update set to be deployed on July 19, the 200th day of the year. I also can’t help but noticed that “07/19” repeats the first three digits of “1973,” and also that the unix timestamp for the date in the UK, where the problem was first spotted, is “11188800,” which is a suspiciously neat number.

Either way: Y2K did happen—in 1973.

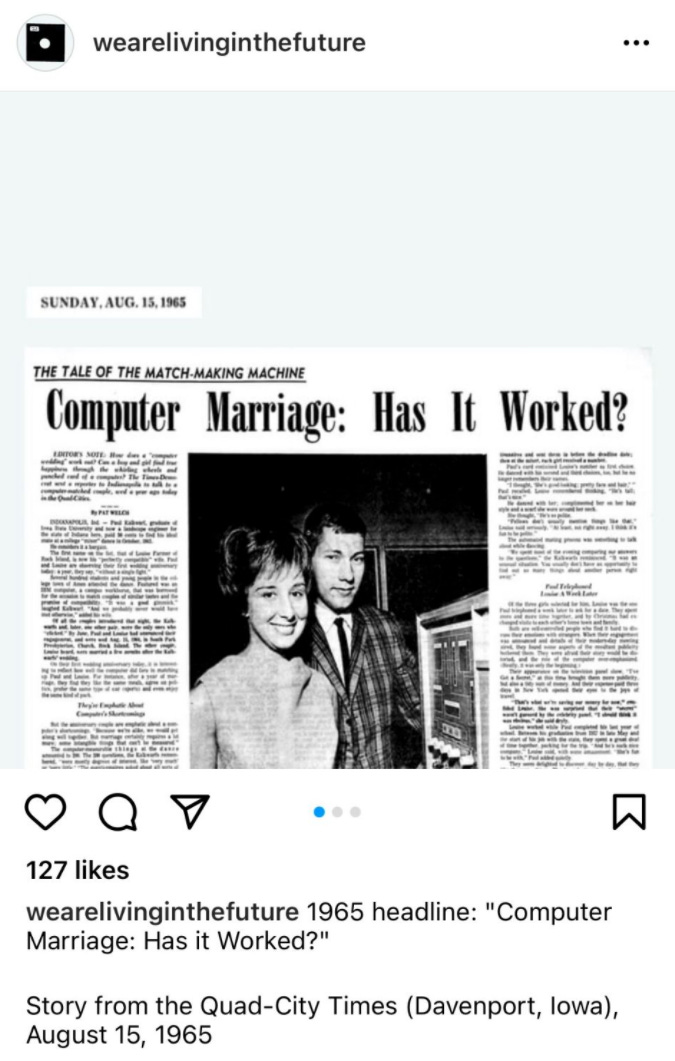

Computer marriage

In 1965, Paul Kalkwarf and Louise Farmer celebrated their one-year anniversary. It was news-worthy because of how they met: They were paired by a computer.

The match-making took place at a college dance, where a computer put Kalkwarf and Farmer together based on their answers to two hundred questions. “The questionnaires asked about all sorts of things,” The Kalkwarfs said. “Hobbies and personal appearance and family background and in what size city you’d want to live.” Paul received a list with three potential matches. He danced with them all, but he was struck by Louise: “I thought, ‘She’s good-looking; pretty face and hair.’” For her part, Louise thought, “He’s tall; that’s nice.” He complimented her scarf, which was a good move. “Fellows don’t usually mention things like that,” Louise said.

“We spent most of the evening comparing our answers to the questions,” they said. “It was an unusual situation. You usually don’t have an opportunity to find out so many things about another person right away.”

A year into their marriage, the couple seemed “delighted to discover, day by day, that they like the same things.” They agreed on furniture (preferring a “simple, modern style of teakwood”), foods (“pork chops, chicken, and casserole dishes” were favorites), cars (“sporty”), and politics (“both voted the same way in the last presidential election”). They’d never had a fight. “Maybe minor disagreements, but voices weren’t raised.”

But they were also eager to clarify that technology didn’t deserve all the credit for their relationship. “Because we’re alike, we would get along well together. But marriage certainly requires a lot more.” In fact, they were skeptical about computer dating as a trend: “Nothing will ever come of it,” they said.

Psssst. Are you new here? Liking it so far? Subscribe to get new posts in your inbox.

DIY “computer”

The Christmas when I was 6 or 7, I wrote Santa asking for a “big computer with lots of games.” I forget what I got that year, but it definitely wasn’t a computer. So I made my own, out of a cardboard box.

This 1970 article profiles two boys, John and David, who did the same thing. A key difference, though: I grew up with relatively small desktop computers, so I made my computer out of a shoebox. John and David, who would have known cabinet-sized minicomputers, went big: They used a motorcycle box. It was covered in aluminum foil and featured “a barbecue pit motor rigged inside” to give off “the put-put sound” and a flashlight for “lighting effects.”

The boys took turns inside the box, playing the part of the machine. “We’ve been doing a lot of studying, history and everything so that we can answer the questions asked the computer as best we can,” said John. “However, if we don’t know an answer we try to bluff our way out of it. Sometimes, if we don’t know the answer, we’ll say ‘maybe’ or something like that.”