Art, music, speech recognition, and computers according to kids

Delightful stories from the history of technology and the humans who use it.

Computers according to kids

In 1970, Data General Corporation, a minicomputer manufacturer, ran a contest challenging children to make art about the computer. What started as a promotional stunt became something akin to an anthropological experiment, capturing the perspective of the first generation of “true inhabitants” of the “electronic space.”

Data General received 600 entries from kids in 5 countries. Several young artists submitted explanatory texts with their pieces. Like Julie (age 8): “The computer is… a pussycat.”

Some other gems:

“Wayne Middleton, Sudbury: Power in a computer is similar to the method of eating good foods to strengthen our bodies.”

“Kimberley Williams, 8, Wayland: Dear people, I love computers. I also love people that make computers. […] I think it is amazing how you make them.”

“Wendy Marie Gerbands, 3, Bedford: The blob in the left-hand corner is the moon—so she says. (From Wendy’s mother.)”

One little boy struck a more ominous tone: “Plans are sure falling apart.” But my personal favorite is this: “What I have made is what I think is inside the computer. There are little men who jump on the switches when you press the keys.”

Psssst. Are you new here? Liking it so far? Subscribe to get new posts in your inbox.

Girls day, boys day

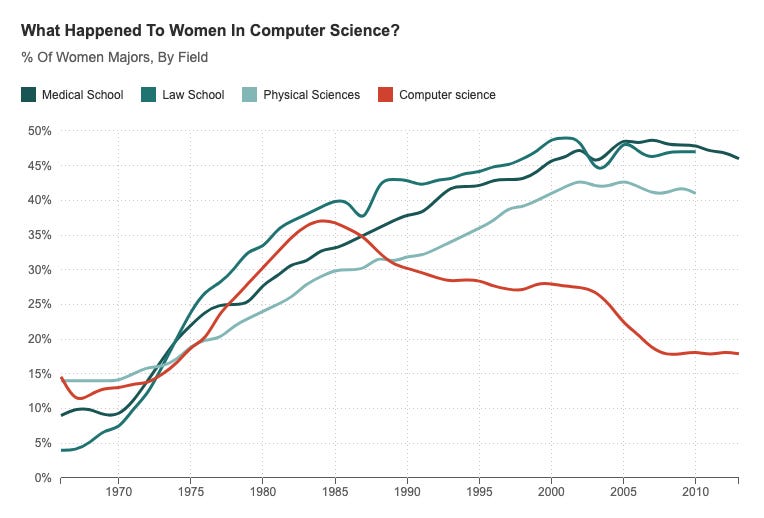

In the 1980s, the number of women studying computer science began to decline, which was strange because the phenomenon was specific to computer science. Other STEM fields, like physical sciences and medicine, saw an uptick in female students. But in computer science, the trend line swerved downwards:

Researchers today believe the decline was caused by a change in culture. The computer-savvy protagonists of 1980s movies like War Games and Revenge of the Nerds were always male, and ads for personal computers showed little boys huddled around a monitor. Computers, the media was saying, were the playthings of boys.

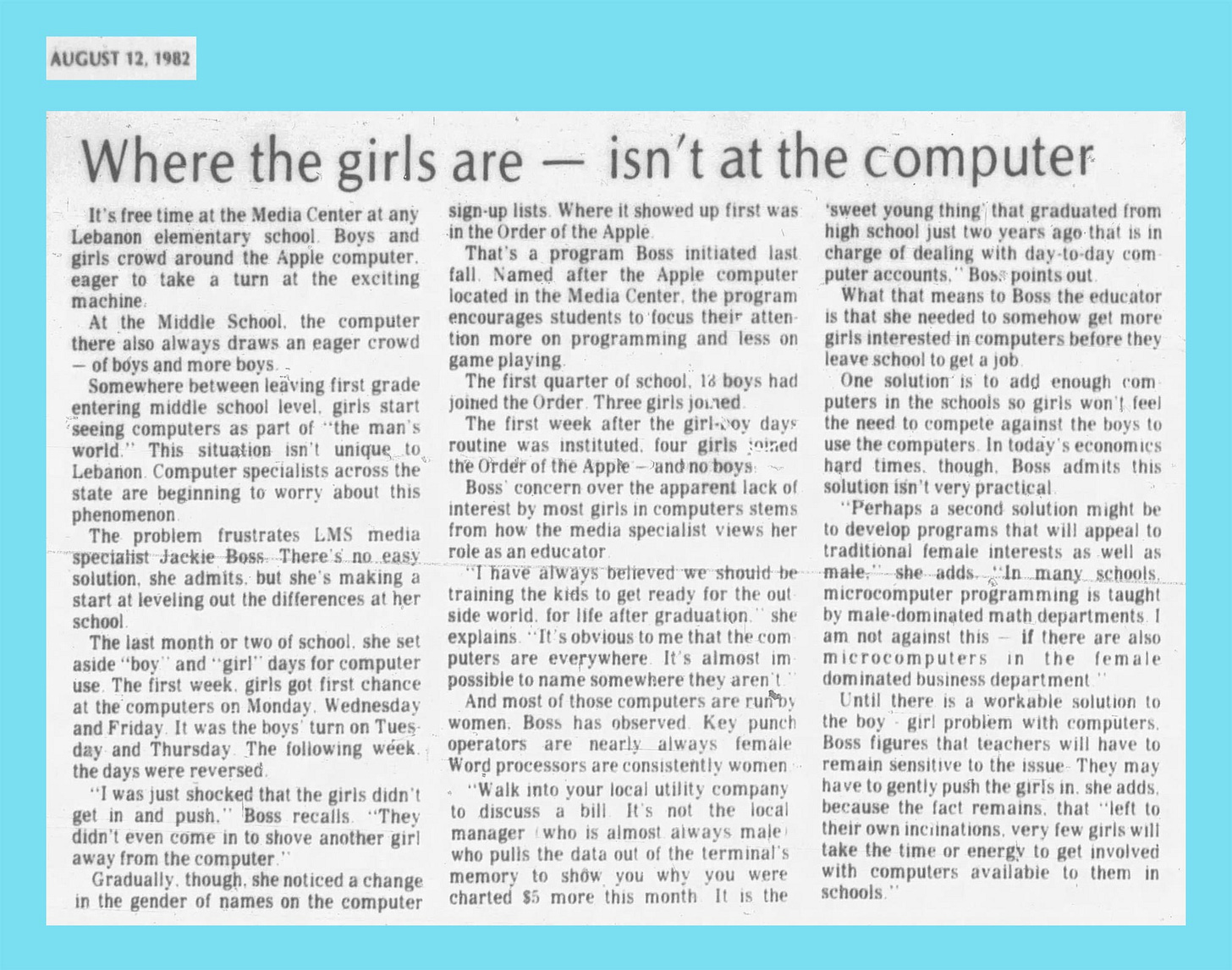

In 1982, a middle school in Lebanon, Oregon, became a microcosm of this phenomenon. During free period, boys were swarming to the computers while girls stayed away. “Somewhere between leaving first grade and entering middle school level, girls start seeing computers as part of ‘the man’s world,’” the article reported.

Unhappy with the “boy-girl probelm with computers,” educator Jackie Boss set up an alternating schedule with “boys days” and “girls days” so each group could have dedicated time with the machines. At first, the girls were hesitant. “I was just shocked that the girls didn’t get in and push,” Boss said. But slowly, more and more girls began using the computers, even joining an after-school club called “The Order of the Apple.” (Because they used computers from Apple. Get it? Get it?)

Speech recognition

For about as long as we’ve been making computers, we’ve been trying to talk to them.

And, well, mostly failing.

The following quote will sound familiar to anyone who has talked to the robot at the other end of the Delta Airlines customer-service line, or who has attempted to use voice to set a timer on their phone only to find themselves fumbling to hang up a call before their ex picked up: “Despite limited success in getting computers to understand words and commands, many researchers concede that no one has a clue about how to get machines to understand general conversation.”

Computer art

This week in 1968, Don Mittleman, director of Notre Dame’s computer center, unveiled a series of oil paintings created with a UNIVAC 1107 computer.

NFTs, hallucinating neural networks, that one time that Thomas Middleditch from Silicon Valley acted in a movie written by an AI program called Benjamin... For as long as we’ve been drawing pictures or making music with machines, we’ve been asking ourselves the same thing: “But is it art?”

The question betrays a certain nervousness about machines encroaching into what we perceive as a quintessentially human activity. We get possessive. Art is ours. Only we can be creative.

Which is… correct! Yes! Of course! Computers aren’t creative; the humans who program them are. We confuse the act of holding a paintbrush with the idea of “being creative,” so when the brush is held by a plotter connected to a computer, we worry that the creativity belongs to the machine. That’s just not true. The 1968 article that reported on Mittleman’s paintings also interviewed the head of the art department at Notre Dame, who compared the role of a programmer to that of an architect: “The fact that the architect produces blue-prints rather than the building itself does not diminish his creative role.” Well put, Mr. Head of Art Department.

Technology is a tool. It can do nothing of its own accord. Even the most sophisticated movie-script-writing neural network has a human behind it. And if you believe that, then “the computer meets the first essential of art, in that it can serve as a medium for human expression,” as the article put it.

Tic-tac-toe

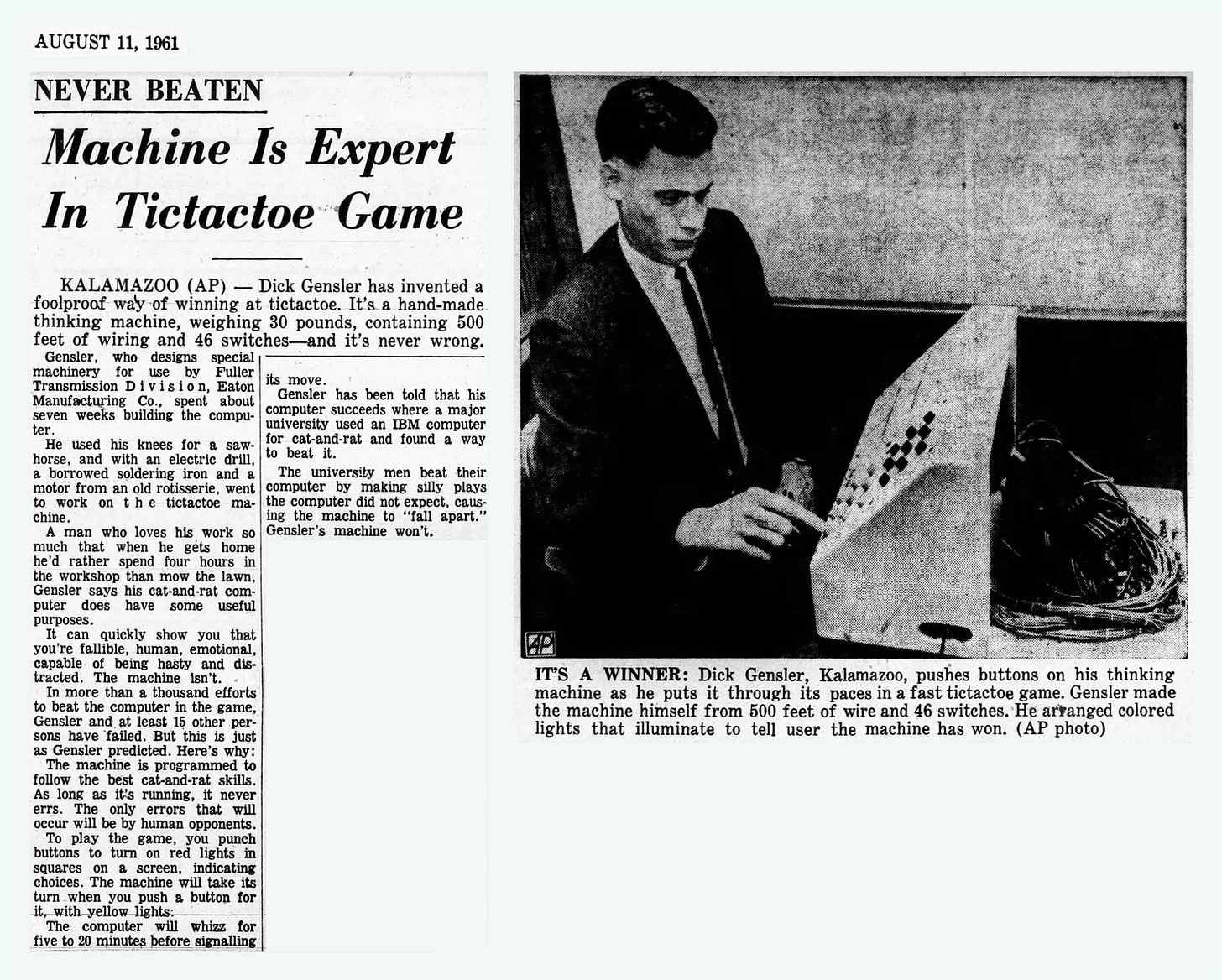

In 1961, a computer hobbyist created a computer that played tic-tac-toe. It was unbeatable, if also slow: each move took the machine “five to 20 minutes.”

We humans are funny. Consider our repeated attempts to create machines that can beat us at games. Chess, Go, arcade games, Starcraft—over and over, we’ve tried our darned hardest to engineer our own defeat.

There are two ways to look at this. The first is that we, as a species, are quite literally self-defeating. (I don’t like that one.) The second is that games, with their rigid rules and limited scope, are one of the few environments where computers can come anywhere close to approximating human proficiency. Sure, there are more possible moves in chess than there are atoms in the universe, but the game is still constrained—the board is an 8x8 grid—and predictable—you make a move, I make a move; the bishop only travels diagonally, etc. These constraints make it a workable environment for a computer.

The real world is infinitely more complex, and humans are infinitely better at handling it. Do you know how I know that? Because here is what happens when a computer encounters an unpredictable environment.

Computer music

The 1980s were a boon for computer music. New hardware let composers do things they couldn’t before: “The latest program being used at MIT allows the composer to change the tempo of a piece by waving a light pen at the screen, much like a conductor leads an orchestra with a baton.”

Some musicians liked computers for their accuracy: “I wrote music for years and never heard a note of it performed properly,” said one. Others felt the machines’ style was sterile, and they adjusted accordingly: “I can program in random deviations, even inaccuracies, that make the sound better. Perfectly produced compositions just don’t sound good.”

Psssst. Are you new here? Liking it so far? Subscribe to get new posts in your inbox.

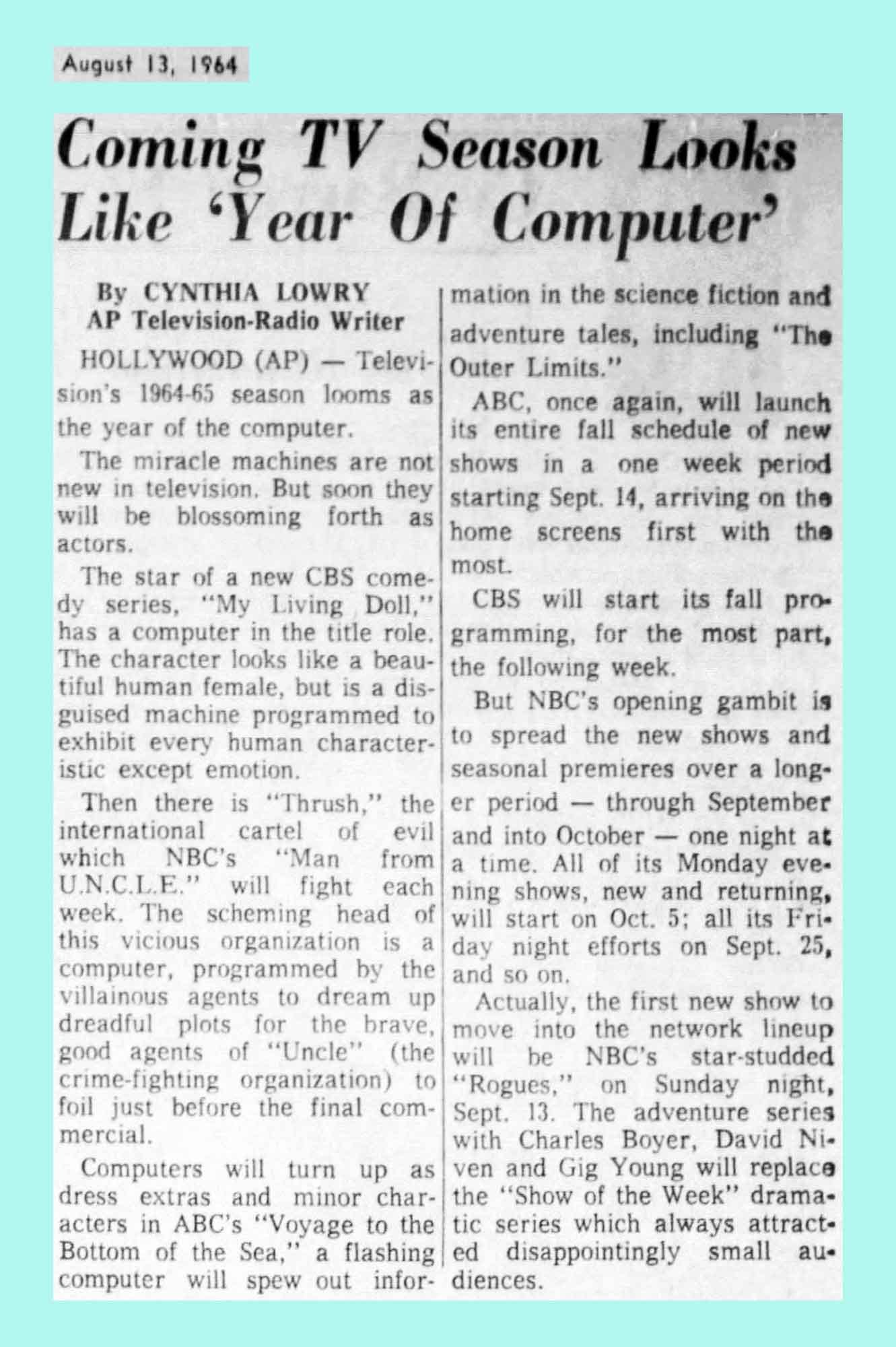

Computers on TV

Popular culture tends to reflect the times. So it made sense that in the sixties, TV shows began featuring computers as characters.

Sometimes, the computers were villains. In The Man from U.N.C.L.E., a malevolent machine ruled over an organization called T.H.R.U.S.H. (which stood, aptly, for “Technological Hierarchy for the Removal of Undesirables and the Subjugation of Humanity”).

Other times, they were protagonists, like the titular character in a show called (and I’m not making this up) My Living Doll. Per Wikipedia, the series followed “a psychiatrist who is given care of Rhoda Miller, a lifelike android (played by Julie Newmar) in the form of a sexy, Amazonian female, by her creator, a scientist who did not want her to fall into the hands of the military.” (Again: Not making this up.)

While The Man from U.N.C.L.E. ran for four years and was eventually repurposed in a 2015 film, My Living Doll was canceled after one season. Shocking.