Computer dating, playing God, and a printer for Chinese

Breaking news from the history of technology and the humans who use it

Computer dating

This week in 1969, a computer-dating company called Compatibility took out a full-page ad trying to persuade singles to “be comfortable with computer dating.”

Compatibility served photos of potential suitors to clients, who could swipe to the left or right to indicate their interest. A mutual right-swipe constituted a “match” and unlocked the ability to carry on a conversation via text entry.

Just kidding! That’s not how Compatibility worked! What do you think relationships are? A game?

Psssst. Are you new here? Liking it so far? Subscribe to get new posts in your inbox.

A woman in tech

This week in 1970: “They don’t realize that a computer is just a high-grade moron that does what you tell it to.”

That was Penny Kaniclides, a computer executive, on why some women tended to “fear” digital technology. “I’d like to see more women alerted to the possibility of a career in computer technology,” she said.

To the best of Kaniclides’ knowledge, she was “the first woman president of a computer company.” She founded her firm, Telstat Systems, after rising through the ranks at Standard & Poor’s, where she went from programmer to the company’s first female vice president. “In that capacity, Penny supervised 85 persons, all males.”

What was her experience like as a woman in tech? “Perhaps because this is such a comparatively new field, I encountered very little, if any, discrimination because I am a woman,” she said. (Now might be a good time to note that the profile begins by remarking on her appearance and ends with her marital prospects, and the headline attempts a pun about her figure. But, you know, 1970.)

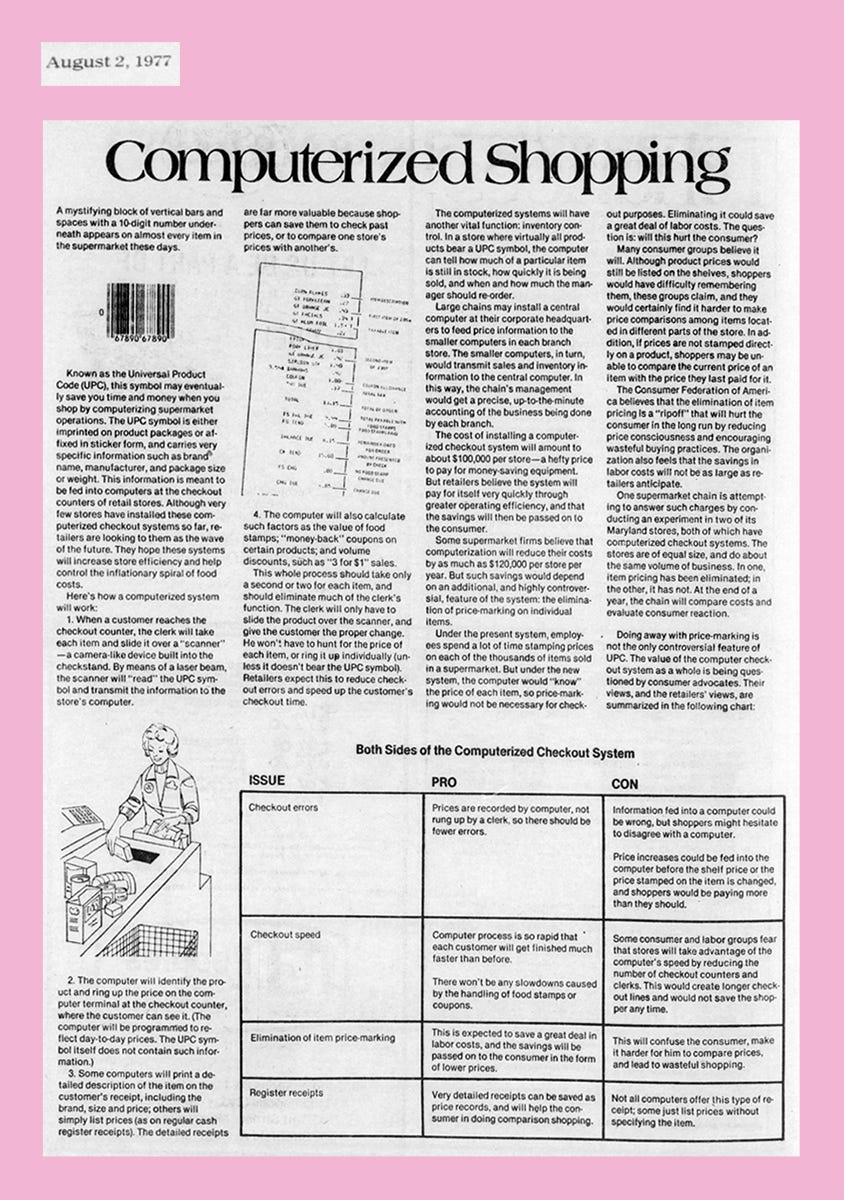

Shopping

This week in 1977: Consider the barcode. It’s so ubiquitous now that it can be hard to imagine it was ever novel. But once upon a time, the barcode was “a mystifying block of bars and spaces with a 10-digit number underneath.”

Mystifying!

Computer at HBCU

This week in 1966: Lincoln University, a HBCU in Missouri, debuted an IBM 1620 computer, “one of the most fascinating educational and research tools” at the school.

“Educational,” sure, but also just fun: “The versatility of the equipment was demonstrated not long ago when a ‘mate selection’ program was conceived and executed. Students were sent questionnaires and asked to list such things as their hobbies, tastes, personal habits, and ambitions. The computer was used to compare characteristics of the men and women students, and on this basis was able to ‘select a mate for each student.’”

Among the computer’s other talents: drawing, writing, and playing blackjack.

Propaganda

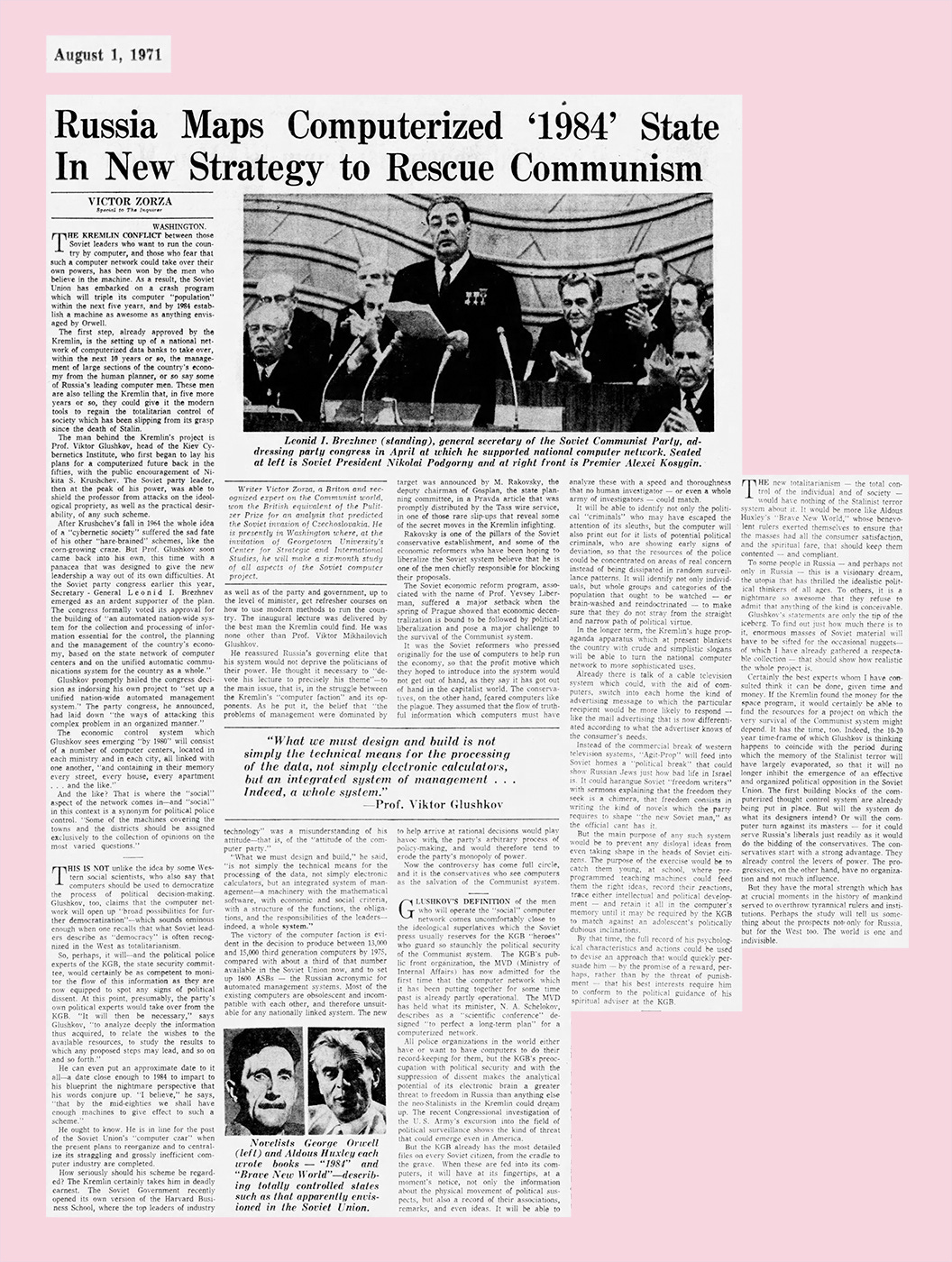

This week in 1971, news of a state computer network under development in the Soviet Union combined two bête noirs of nineteen-seventies America: computerization and communism.

“Already there is talk of a cable television system which could, with the aid of computers, switch into each home the kind of advertising message to which the particular recipient would be more likely to respond.”

Hmmm. Russia using computers to serve tendentious hyper-targeted “news” to sway people… why does that sound familiar?

Playing God

This week in 1979: “These things are fantastic, you can do almost anything with them,” said one member of the Vermont Computer Guild at their weekly meeting. He had programmed a computer to “specify the day of the week for every date since 1752.” Another guild member was showcasing a game called “Life,” a proto-Civilization where “213 generations of people” could “live and die in a matter of minutes.” And a third had rigged a synthesizer to play Bach (“he doesn’t play keyboard himself—he lets the computer do it”).

“It’s just like God,” said one of the guild members. “You set it (the computer program) up and wait to see what happens, and laugh at your own private universe.”

Psssst. Are you new here? Liking it so far? Subscribe to get new posts in your inbox.

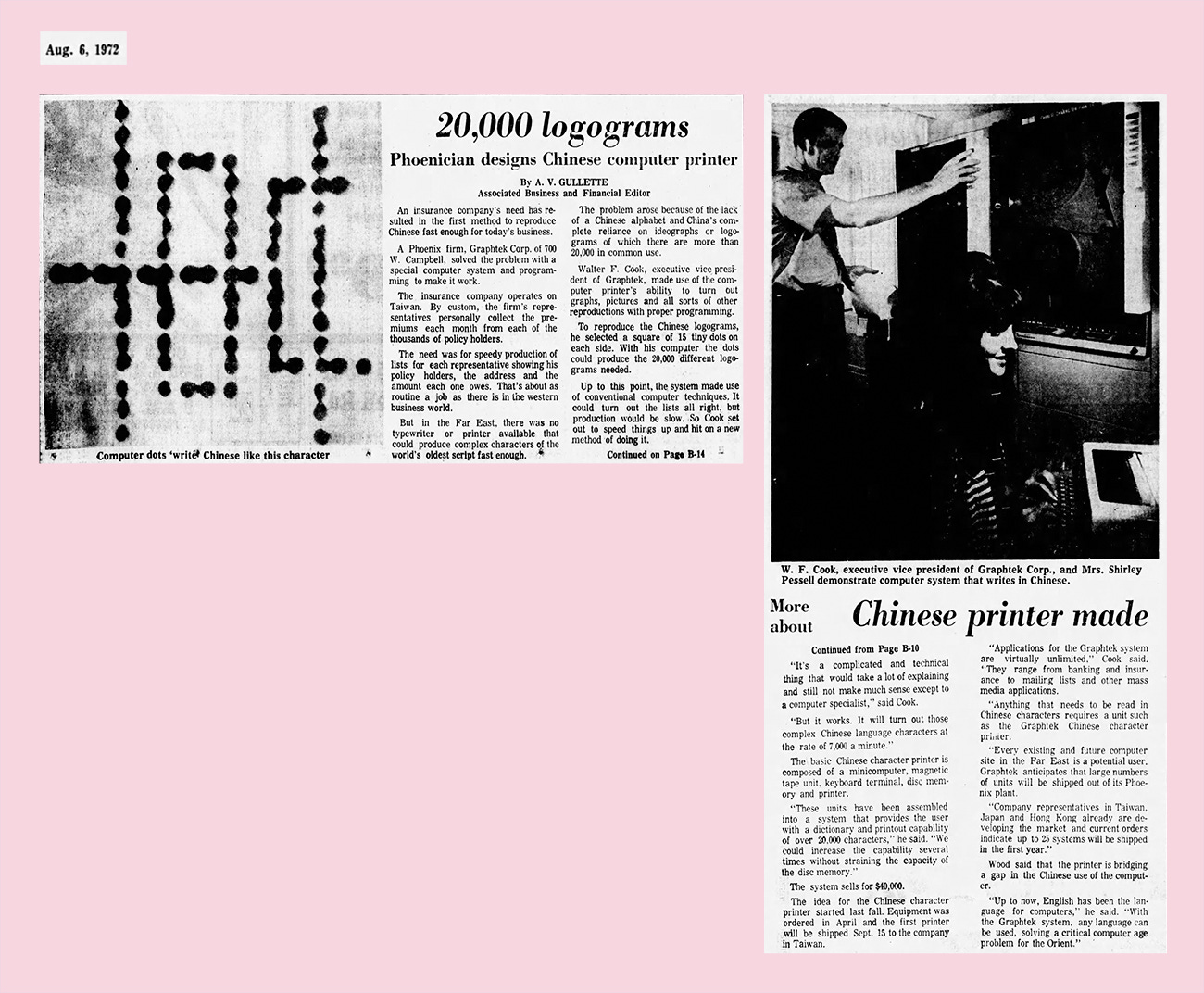

Chinese printer

This week in 1972: Graphtek, a firm in Arizona, developed a printer capable of generating Chinese characters from a dot matrix. This may not sound like a big deal, but think about this: the software you’re using to read this newsletter was most likely written in a programming language that uses the Latin alphabet.

And it’s not just your browser or email client. All of the most widely used programming languages were constructed with literal ABCs. Exceptions exist, but they’re, well, exceptions. The Latin alphabet has been the default character set for tech development since the ENIAC in the 1940s.

China is a hotbed of tech development today, but its entry into the digital revolution was delayed for one very basic reason: The tens of thousands of characters in the Chinese language were simply not accounted for in early software and hardware. (RadioLab has a great episode on one man’s decades-long effort to create a Chinese-language keyboard.)

The idea for the Graphtek Chinese printer came from a client in Taiwan, an insurance company that needed to quickly generate monthly reports with their policyholders’ information.

“Up to now, English has been the language for computers,” said the engineer responsible for the project. “With the Graphtek system, any language can be used, solving a critical computer age problem for the Orient.”